BY: JENNIFER LEE

The Dining Room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, formerly the Members Dining Room, opened to the public for the first time in mid-2017. If you were not aware that the Met had a members-only dining room, then you are not alone: it was notoriously well-hidden, requiring visitors to navigate several extensive galleries on the ground floor and take an elevator from the European Sculpture Galleries to the fourth floor. Members who successfully completed this odyssey through world art were treated to a meal in a quiet dining room whose huge glass windows overlook Central Park.

The restaurant, rechristened the Dining Room at the Met, will now take your money whether you have a membership or not, from 12-2:30 on weekdays, on Friday and Saturday nights, and for Sunday brunch. By all accounts, opening up the restaurant and the resulting press has livened up the dining room considerably.

Was it ridiculous for a twenty-first century public institution to maintain a separate restaurant for its members? Arguably, yes, so opening the restaurant might be taken as more pragmatic than political: a statement for economics, not access. But what’s changed since the restaurant’s inception in 1991 to make a members’ dining room untenable, and what does this move say about the Met and the way we think about museum visitors?

|

| Grilled octopus from the Dining Room menu, now available to any visitor with $21 (plus tax and tip) and a blazer. Source. |

This development

comes at an interesting time in the Met’s history; it’s been dogged by deficits as it undergoes a sea change in institutional culture, and recently announced in a spectacularly unpopular move that it would introduce mandatory admissions

fees for out-of-town visitors. Previously, admission to the museum was pay-what-you-wish

at the door: anyone willing to stand in line could enjoy the Met at whatever

price point they felt was appropriate.

It’s

important to read the existence of the Members’ Dining Room in this context. Providing

a service limited to members only is a good way to convince people to pay for membership

when they know that they can get in for free. (Annual

membership to the museum currently starts at $100 USD, more or less on par with

institutions like the ROM or the AGO but higher than other New York

institutions such as the Whitney, MoMA, or the Guggenheim, which all charge for

admission.)

The few other major institutions that maintain exclusive food and

drink facilities for members – the British Museum and the V&A among them –

work on a free-admission model and are crowded with visitors, so offering a

quiet place to sit can help to justify buying a membership to a nominally-free

museum. The Met, indeed, continues to maintain a member’s lounge and rooftop

bar. However, ending a perk which was underused even by members seems like a

natural move for a museum which struggles to stay both relevant and solvent.

|

|

| The Dining Room at the Met. Does the stunning view save the restaurant’s otherwise humdrum décor? Source. |

The Dining Room is the only one of the Met’s dining options with a designated dress code (smart casual), and the most expensive by far. Brunch, available through a prix fixe menu only, will run you $55, and dinner for two could easily cost several hundred. This is not, of course, astronomical for a meal in New York, but it does raise the question: is this restaurant really so much more accessible than before? How many people are going to eat here who would be unable to afford a museum membership?

Perhaps it’s the optics of exclusivity, rather than the economics, which makes for inaccessibility in this case. The democratic rhetoric of the twenty-first century is that museums are there for everyone to enjoy, and the more exclusive the perks available to – let’s be honest – rich people, the more uneasy we feel about them. This is a problem for institutions which are trying to balance wide public accessibility with the feeling of exclusivity and belonging that drives membership sales.

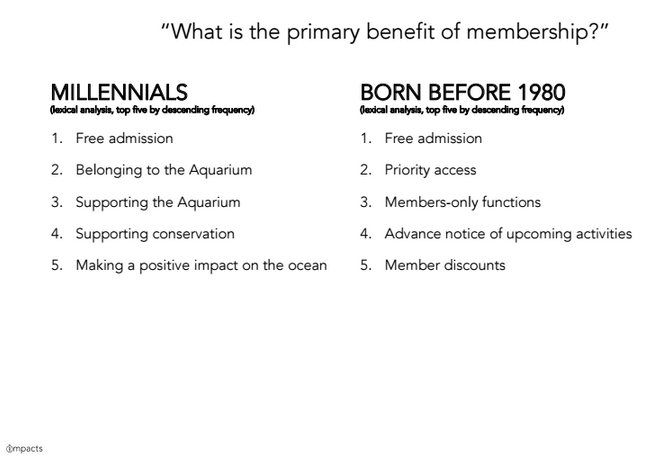

Millennials, in particular, invest in non-profit membership for completely different reasons to the generations before us: we’re interested in seeing the impact of our money and supporting a cause, while those born before 1980 want VIP treatment.

So opening up the Dining Room makes a statement that this museum is, in fact, for us; it recognizes that young audiences want a different experience at the museum than their parents and grandparents, and that it's possible to love and support a museum without investing in membership.

Time will tell whether young patrons take to the restaurant, although I suspect that the museum might need to consider a gentle redesign if it wants to attract an Instagram-happy crowd. The Dining Room’s décor is fairly underwhelming: beige walls, beige carpet and rather dowdy wall sconces make it feel more like a mid-1990s hotel lobby, or the Scarborough dim sum restaurants of my youth, than an exclusive Manhattan hotspot. Like an astonishing number of museum restaurants, it is devoid of the very thing patrons have come to see, i.e. art. If it can find the money, the Met might want to take a leaf from the books of art museums like the Guggenheim, the Centre Pompidou, or the new gallery on the block, the National Gallery of Singapore, all of which boast restaurants which are attractions in their own right.

|

| The primary benefits of aquarium membership, according to millennials and non-millennials. Source. |

So opening up the Dining Room makes a statement that this museum is, in fact, for us; it recognizes that young audiences want a different experience at the museum than their parents and grandparents, and that it's possible to love and support a museum without investing in membership.

Time will tell whether young patrons take to the restaurant, although I suspect that the museum might need to consider a gentle redesign if it wants to attract an Instagram-happy crowd. The Dining Room’s décor is fairly underwhelming: beige walls, beige carpet and rather dowdy wall sconces make it feel more like a mid-1990s hotel lobby, or the Scarborough dim sum restaurants of my youth, than an exclusive Manhattan hotspot. Like an astonishing number of museum restaurants, it is devoid of the very thing patrons have come to see, i.e. art. If it can find the money, the Met might want to take a leaf from the books of art museums like the Guggenheim, the Centre Pompidou, or the new gallery on the block, the National Gallery of Singapore, all of which boast restaurants which are attractions in their own right.

|

| National Kitchen by Violet Oon, a ridiculously beautiful restaurant serving Singaporean favourites at the National Gallery of Singapore. I mean, can you even. Source. |

While older patrons may be content with beige carpet and a good view, the combination of good food and beautiful surroundings are especially important to the 20- and 30-somethings

that museums are desperately trying to attract. People visit museums to be surrounded by beauty, and also to take pictures and put them on social media so that other people know how cultured they are, and they visit high-end restaurants for the same reasons. The Met has yet to catch on, but at least they've got good natural light.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.