BY: JENNIFER LEE

Delectable readers, our time has come: this is my last Musings article. Thank you for joining me at the table this year as I explored food in and out of museums and libraries. As my colleagues and I leave the iSchool and get ready to move up to the grown-ups’ table, I’d like to propose a toast. While I have your attention, and while our champagne flutes, wine glasses, and teacups are raised, perhaps we can use this last column to ponder an area of food history that I’ve neglected a little: the history and politics of drink.

I hope that I’ve managed to convince you in this column that food is political. What we eat (and what we don’t eat), when and how we eat it, how we talk about it, and who gets invited to sit at the table are not random happenstance, but the end results of historical processes that have been working for decades, centuries, or even millennia. Of course, drinks are political for the same reasons. What we serve, where it comes from, and who is drinking are all worth thinking, talking, and museum-ing about, because they tell us a lot about ourselves.

What is a museum for, if not to tell us about ourselves?

I propose three ideas to bring drink history into the museum in ways that matter now and will matter more and more in the future. Gentle reader, let us slake the public’s thirst for knowledge together.

1. Make your narratives inclusive

Everyone needs to drink something, and all kinds of people have been involved in making and serving drinks. We’ve already talked about the work that Teresa McCulla is doing at the Smithsonian to diversify the history of early American beer brewing, bringing to light the role of women, enslaved people, and immigrants. When we research and talk about members of historically disenfranchised groups and their work, we emphasise their agency and make the stories we tell more interesting, more diverse, and more true to historical fact.

2. Find the politics in the everyday object

I’ve told everyone I know about this incredible article in Lapham’s Quarterly. Patricia A. Matthew writes about the late 18th-century consumer movement to boycott sugar from slave plantations. In the material record, this manifested as teapots and drinking utensils with snappy anti-slavery slogans, which allowed British women to organize around a political cause when they were not permitted to vote. Although we tend to think of teapots as the most domestic and innocuous of objects, their use speaks to complex issues of gender, colonialism, class, and globalization. Spin out the meanings of everyday objects, and you will often find that they have been more controversial than you think.

3. Make a political statement.

It is not an accident that the communities without access to safe drinking water are disproportionately poor and non-white. In Canada, 107 First Nations reserves were affected by boil-water advisories at the end of last year. In the United States, citizens and water protectors are still fighting for access and regulation, and against fracking and pipelines, in communities like Standing Rock and Flint. Governments, regulatory bodies, and corporations have failed these communities. In a few decades we may all be in their position, with our access to fresh water jeopardized by government mismanagement and corporate interests.

Museums must work toward water justice – for disenfranchised communities now and for everyone in posterity. There are many ways to do this: through advocacy, ensuring that organizations obtain and sell water in ethical ways (Nestle’s water operation in Michigan, for example, violates a treaty which protects the land for Grand Traverse Band and Saginaw Chippewa tribal use), and, of course, through the interpretation of art and objects.

The AGO’s acquisition and display of Ruth Cuthand’s arresting piece Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink drew attention to the water crisis on reservations across Canada. Unless we resolve the inequalities that persist around access to safe drinking water, drawing attention to water justice and empowering visitors to act will only become more important in the future. While some necessary action, including divesting from fossil fuels and selling ethically-obtained water, represent big changes for museums, mindful acquisition and display of objects which speak to inequality is not only a possibility but a duty.

Cheers, santé, and prost, Musings readers! This is my final Musings column; it’s been a pleasure to connect with you and with my wonderful fellow columnists this year. Stay hungry, thirst after knowledge, and feed your souls. I’ll see you around the table.

Delectable readers, our time has come: this is my last Musings article. Thank you for joining me at the table this year as I explored food in and out of museums and libraries. As my colleagues and I leave the iSchool and get ready to move up to the grown-ups’ table, I’d like to propose a toast. While I have your attention, and while our champagne flutes, wine glasses, and teacups are raised, perhaps we can use this last column to ponder an area of food history that I’ve neglected a little: the history and politics of drink.

I hope that I’ve managed to convince you in this column that food is political. What we eat (and what we don’t eat), when and how we eat it, how we talk about it, and who gets invited to sit at the table are not random happenstance, but the end results of historical processes that have been working for decades, centuries, or even millennia. Of course, drinks are political for the same reasons. What we serve, where it comes from, and who is drinking are all worth thinking, talking, and museum-ing about, because they tell us a lot about ourselves.

What is a museum for, if not to tell us about ourselves?

|

| W.D. Cooper's engraving of the Boston Tea Party demonstrates how political a drink can be. Source. |

I propose three ideas to bring drink history into the museum in ways that matter now and will matter more and more in the future. Gentle reader, let us slake the public’s thirst for knowledge together.

1. Make your narratives inclusive

Everyone needs to drink something, and all kinds of people have been involved in making and serving drinks. We’ve already talked about the work that Teresa McCulla is doing at the Smithsonian to diversify the history of early American beer brewing, bringing to light the role of women, enslaved people, and immigrants. When we research and talk about members of historically disenfranchised groups and their work, we emphasise their agency and make the stories we tell more interesting, more diverse, and more true to historical fact.

|

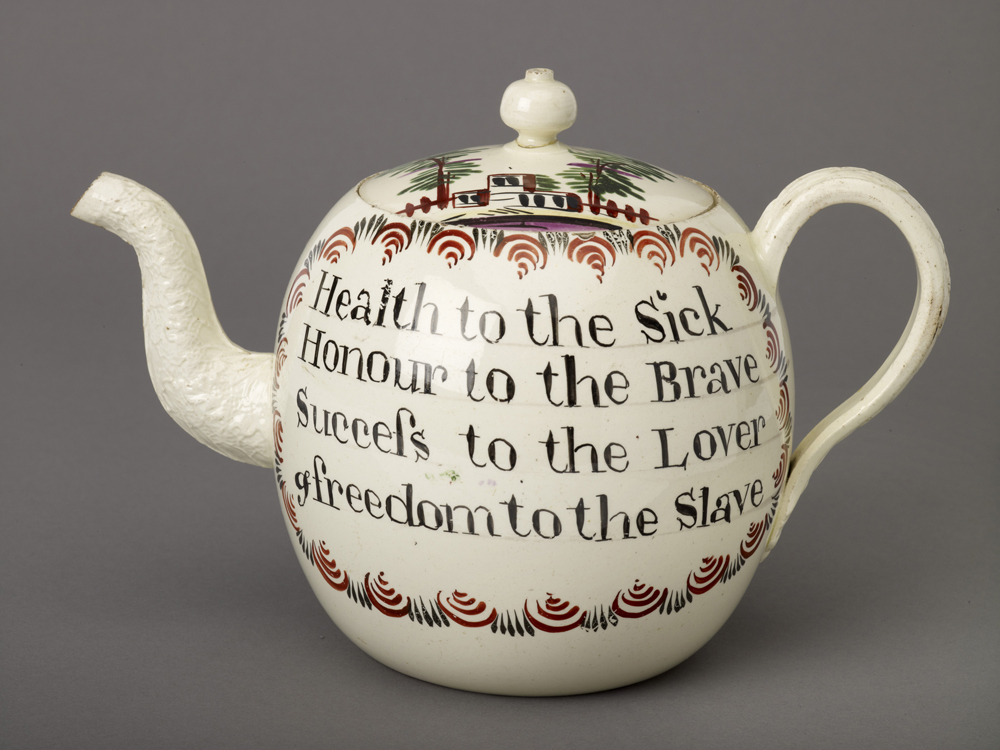

| Abolition Teapot, by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, c. 1760. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Source. |

2. Find the politics in the everyday object

I’ve told everyone I know about this incredible article in Lapham’s Quarterly. Patricia A. Matthew writes about the late 18th-century consumer movement to boycott sugar from slave plantations. In the material record, this manifested as teapots and drinking utensils with snappy anti-slavery slogans, which allowed British women to organize around a political cause when they were not permitted to vote. Although we tend to think of teapots as the most domestic and innocuous of objects, their use speaks to complex issues of gender, colonialism, class, and globalization. Spin out the meanings of everyday objects, and you will often find that they have been more controversial than you think.

3. Make a political statement.

|

| Indigenous water protectors protest the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, ND; oil pipelines endanger drinking water and coastlines in addition to violating treaties. Source. |

It is not an accident that the communities without access to safe drinking water are disproportionately poor and non-white. In Canada, 107 First Nations reserves were affected by boil-water advisories at the end of last year. In the United States, citizens and water protectors are still fighting for access and regulation, and against fracking and pipelines, in communities like Standing Rock and Flint. Governments, regulatory bodies, and corporations have failed these communities. In a few decades we may all be in their position, with our access to fresh water jeopardized by government mismanagement and corporate interests.

Museums must work toward water justice – for disenfranchised communities now and for everyone in posterity. There are many ways to do this: through advocacy, ensuring that organizations obtain and sell water in ethical ways (Nestle’s water operation in Michigan, for example, violates a treaty which protects the land for Grand Traverse Band and Saginaw Chippewa tribal use), and, of course, through the interpretation of art and objects.

|

| Ruth Cuthand's Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink highlights the First Nations water crisis in Canada. 2016. Source. |

Cheers, santé, and prost, Musings readers! This is my final Musings column; it’s been a pleasure to connect with you and with my wonderful fellow columnists this year. Stay hungry, thirst after knowledge, and feed your souls. I’ll see you around the table.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.