OBJECT OF THE WEEK

BY: NATANIA SHERMAN

There’s something to be said for the allure of objects. The world is full of things that inspire our desire, sentiment, nostalgia and countless other emotions. I, myself form deep emotional attachments to inanimate objects, and a major part of my attraction to Museum Studies was a love and passion for objects. Being part of a consumer society means living with stuff. There is no piece of art or design that reveals our complicated relationship with our stuff quite as much as the Surrealist dream object.

The Surrealist dream object has its origins in the book L'Amour Fou, published in 1937, by poet André Breton, de-facto leader of the Surrealist movement. Breton describes coming across a “slipper spoon” in a flea market. The “slipper spoon” is a tiny spoon like-object that might be used as a shoehorn. André Breton didn’t know exactly what it was, only that when he saw it, he was overwhelmed with a sense of déja-vu, because the obscure little spoon was an artifact from his dreams (Malt 77). Breton then went on to write rapturous stories about his experience of finding the "slipper spoon."

|

| Andre Breton's slipper spoon, photographed by Man Ray (Image Source) |

Breton was not a visual artist, he was a poet and writer, but his ideas about dream objects resonated with the group of artists and poets who would come to form the Surrealists in the years between World War I and World War II from 1919 until 1939. In Surrealist art, there are many incarnations of the dream object. The Surrealists, influenced by the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis, began to create artistic experiments based on dreams, and the element of chance. The dream object engages with both of these ideas because it is something that one finds through luck, and its power lies in the objects’ impact on the finder’s imagination (Malt 78). The act of confronting a dream object is much like browsing a department store for something that you can’t quite describe until you find yourself in it's presence. Some artists interpreted Breton’s ideas as found objects, and used junk shop ephemera in their art. Eventually many artists began to create their own dream objects out of composites of other items. These fabricated dream objects were likewise a response to André Breton’s ideas. “I recently proposed to fabricate, in so far as possible, certain objects which are approached only in dreams… To throw further discredit on those creatures and things of reason” (Ades 73). The resulting sculptures, in Breton’s words, are as “beautiful as the chance encounter of the sewing machine and the umbrella on a dissecting table.”

My personal favourite of these composite dream objects is Meret Oppenheim’s Fur Cup also known as Breakfast in Fur from 1936. The sensuality of this fur lined teacup is tinged with disgust, because despite the teacups inherent beauty, try to drink from it and you’re in for a surprise!

|

| Breakfast in Fur by Meret Oppenheim from 1936 (Image Source) |

The breadth of the Surrealist dream object doesn’t stop at sculpture. The Surrealists dabbled in the commercial world as well (Wood 2). Elsa Schiaparelli, a prominent fashion designer at the time, incorporated Surrealist visual language into her couture collections, most notably in a series of shoe hats inspired by the drawings of painter, Salvador Dali, and in the packaging for her perfume, aptly named for the Surrealist raison d'etre, "Shocking."

|

| Chapeau by Schiaparelli from 1937-8 (Image Source) |

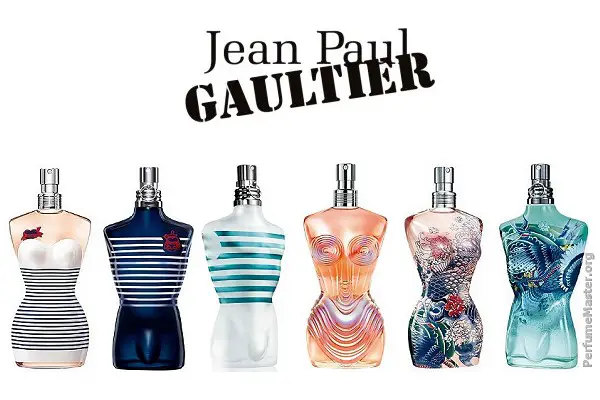

There has always been a tension in surrealist visual language between high art and commercial art. Even today, the legacy of the composite dream object exists in designer goods for consumption. One need only look in the perfume section of your local department store to see the impact that the Surrealist imagination has had on today’s design world.

|

| Designer Jean Paul Gaultier's perfume bottles referencing a Schiaparelli design (Image source) |

The surrealist dream object is a stand in for our desires. On the one hand, objects are an anchor. Their allure lies in their sensuality and ability to ground us in the physical world. On the other hand, objects allow us to travel through time. They can inspire dreams of the future or nostalgia for the past. The objects in our dreams take on many forms, and the sense of recognition that André Breton describes upon first seeing his slipper spoon is one I’m sure many of us have once felt. It can happen in a sample sale downtown, a flea market in the suburbs or a collections vault in a museum. We are surrounded by objects both useful and otherwise, and if we can understand their power to enthral us, then we can begin to better understand ourselves.

Sources:

Ades, D. “Surrealism: Fetishism’s Job.” In Fetishism: Visualizing Power and Desire. London: The South Bank Centre; Brighton: Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, 1995, pp. 67-87.

Breton, André, "L'amour Fou/Mad Love" trans. May Anne Caws, Bison Books; Reprint edition 1988.

Malt J. “ The Surrealist Object in Theory.” In Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, pp.76-112.

Wood, Ghislaine ed. "Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design" V & A Publications, 2007.

Ades, D. “Surrealism: Fetishism’s Job.” In Fetishism: Visualizing Power and Desire. London: The South Bank Centre; Brighton: Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, 1995, pp. 67-87.

Breton, André, "L'amour Fou/Mad Love" trans. May Anne Caws, Bison Books; Reprint edition 1988.

Malt J. “ The Surrealist Object in Theory.” In Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, pp.76-112.

Wood, Ghislaine ed. "Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design" V & A Publications, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.